In Maale Adumim facing the panoramic view of the hills of Jerusalem sits a building that houses the art of Israeli artist Moshe Castel. Castel himself chose the site located between Jerusalem and the Judean desert symbolizing Israel’s past and future and his own connection to Jerusalem and the land of Israel and its history. (http://www.castelmuseum.com) The Israeli architect David Resnick designed the building with input from Castel. Resnick is well known for other architectural landmarks, Yad Kennedy, the “Mushroom” synagogue at Hebrew University, Givat Ram and the Mormon university in Jerusalem.

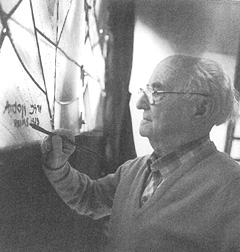

Moshe Castel (1909-1991) was born in Jerusalem to a Sephardi family from Castile with roots that go back to the expulsion from Spain in 1492. At the age of 13 he began to study at the recently opened Bezalel Art School where he learned the rudiments of painting and painted locally inspired landscapes and images. In 1927 at age 17 he traveled to Paris to study at the Academie Julian. Quickly he exchanged his hat and black tie for vagabond clothing and hung out with his fellow artists in the cafes. He rented a small apartment above the sculptor Giacomettti and joined the circle of great artists, Picasso, Matisse, Miro, Soutine and Chagall.

At the Louvre, he sat before the works of the Old Masters and copied their paintings, paying attention to the technique of layering the paint on the canvas. There Castel learned “That art is not symbolic, but rather material, the material is the main thing, the way the paint is placed, the way the layers are placed on the picture, this is the most essential thing.”

In the 1940s he returned to Israel, settled in the Artist Colony of Tzfat and established the New Horizons group of artists that broke way from the established Artists’ Union to focus on universal artistic elements and a more abstract European style. You can visit the house he lived in, newly renovated as a gallery.

In the 1940s he returned to Israel, settled in the Artist Colony of Tzfat and established the New Horizons group of artists that broke way from the established Artists’ Union to focus on universal artistic elements and a more abstract European style. You can visit the house he lived in, newly renovated as a gallery.

He found basalt rocks on his hikes through the Galilee, in the area of Korazim, and began to use them as raw material – the stones were crushed, mixed with a bonding agent and pigment and applied in a thick coat with a palate knife. This material was applied as the textured background for scrolls, letters, figures that became his signature and unique artwork.

There are three other museums in Israel that are dedicated to the works of a single artist. The former residence of the Israeli painter Reuven Rubin at 14 Bialik Street in the heart of Tel Aviv has been made into a museum that displays his paintings from the different periods in his artistic development and preserves the artist’s studio. There is also an audio-visual slide show on Rubin’s life and work. (http://www.rubinmuseum.org.il/home.asp)

The Nahum Gutman Museum was opened to the public at the reconstructed Writers’ House at 21 Rokach Street in Neve Zedek in 1998 and encompasses works in oil, gouache and watercolor, as well as several thousand drawings and illustrations. (http://www.gutmanmuseum.co.il/Default.aspx)

The Janco Dada Museum in the center of the Ein Hod Artists’ Village south of Haifa exhibits the prolific work of Marcel Janco chronologically from his early works as a boy of fifteen. (http://www.jancodada.co.il/en/ar_01.php)

For other museums in Israel check out http://ilmuseums.com/