The Tachana (“Station”) complex includes the historic train station built in 1892, the freight terminal, German Templer Hugo Wieland’s tile factory and cement works and the Wieland family’s home. Today the complex has been renovated and houses restaurants and cafes, fashion, art, antique and jewelry boutiques, a large art bookstore, galleries and every Friday an organic food market. Notwithstanding the commercial aspect, it’s still a historic site and standing on the station platform it’s easy to imagine being transported back to a time of steam engines, pilgrims and pioneers.

The German Templers Society (Tempelgesellschaft) were a Protestant sect who originally settled in Haifa and established the German Colony there; subsequently they built settlements in Sarona and Jerusalem. After the visit of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1899, another wave of pioneers founded Wilhelma, Walhalla, Bet Lehem HaGlilit and Waldheim. The colony’s oranges were the first to carry a “Jaffa Orange” brand, one of the better known agricultural brands in Europe, used to market Israeli oranges to this day. The Templers established a regular coach service between Haifa and other cities and made an important contribution to road construction. They were architects and engineers, ran hotels, beer gardens and promoted the country’s tourist industry.

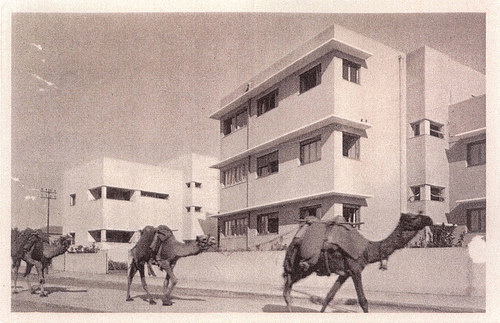

The Wieland family came to Israel in 1900 and established its building materials factory beside the Jaffa train station and the nearby Templer neighborhood. The patriarch, Hugo Wieland, built the villa in 1902 as a single storey structure; a second storey was added a few years later to accommodate the family of 12. The building was designed in the Templer style, stone buildings with a tile roof, wooden shutters, balcony. The front room served as a lounge and was the most beautiful and impressive room in the house, it had a painted ceiling and coal fireplace for heating. The floors were made of decorative tiles produced by the family factory.

During restoration work, some paintings of scenes of women, drinking and dancing, were discovered on walls in one of the rooms. Originally the thought was that these were copies of caricatures from a German magazine. In further investigation it was discovered that these painting were done by Gerd Rothschild, partner with Zev Lipman in Roli Graphic Studio, between 1942-1946. Rothschild learned graphic design in the first class of the Bezalel School of Art in Jerusalem. He was enlisted into the British army as a cook but when his artistic talent was discovered he wandered from British base to base in the region – Palestine, Libya, Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon and Cyprus painting on walls. In later years, Rothschild used art therapy to work with children with disabilities and painted murals in pediatric psychiatric wards. He died in 1991 at the age 72. The British used the buildings in the Jaffa rail yard as a base for supplies after the German Templers were deported to Australia during WWII.

During restoration work, some paintings of scenes of women, drinking and dancing, were discovered on walls in one of the rooms. Originally the thought was that these were copies of caricatures from a German magazine. In further investigation it was discovered that these painting were done by Gerd Rothschild, partner with Zev Lipman in Roli Graphic Studio, between 1942-1946. Rothschild learned graphic design in the first class of the Bezalel School of Art in Jerusalem. He was enlisted into the British army as a cook but when his artistic talent was discovered he wandered from British base to base in the region – Palestine, Libya, Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon and Cyprus painting on walls. In later years, Rothschild used art therapy to work with children with disabilities and painted murals in pediatric psychiatric wards. He died in 1991 at the age 72. The British used the buildings in the Jaffa rail yard as a base for supplies after the German Templers were deported to Australia during WWII.

Another atmospheric building is the Red House, an example of typical Arab construction in the Jaffa area that got its name from the red plaster used on its walls. This building was probably built before the Wieland villa as part of the Manshiya neighborhood, adjacent to the train station complex. A unique feature is the western entrance accented with chiseled sandstone left unplastered which frames the symmetrical series of three openings. Two round openings on the facade, common in Arab buildings are for ventilation.