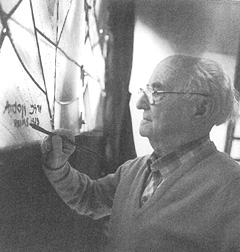

Mordecai Ardon (1896-1992) was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Tuchów, Galicia (then Austria-Hungary, now Poland) but lived a secular life. From 1921 to 1924 Ardon studied at the Bauhaus under Klee, Kandinsky, Feininger and Itten. The influence of the Bauhaus and especially Paul Klee on his artistic development was profound. After graduating from the Bauhaus he studied the painting techniques of the Old Masters, especially Rembrandt and El Greco under Max Doerner in Munich. Combining these seemingly contradictory techniques gives Ardon’s colors their depth and richness.

Mordecai Ardon (1896-1992) was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Tuchów, Galicia (then Austria-Hungary, now Poland) but lived a secular life. From 1921 to 1924 Ardon studied at the Bauhaus under Klee, Kandinsky, Feininger and Itten. The influence of the Bauhaus and especially Paul Klee on his artistic development was profound. After graduating from the Bauhaus he studied the painting techniques of the Old Masters, especially Rembrandt and El Greco under Max Doerner in Munich. Combining these seemingly contradictory techniques gives Ardon’s colors their depth and richness.

In 1933 he immigrated to Palestine under the British Mandate. He joined the faculty of the newly formed Bezalel Arts and Crafts School in 1935, five years later he was elected director. Through the fifties he lectured at the Hebrew University on art appreciation and was artistic advisor to the Israel Ministry of Education and Culture.

Professor Ronen, of Tel Aviv University in speaking of Ardon said:

Ardon conceived colour as possessing an absolute aesthetic and spiritual value. He therefore always strove to create the most beautiful colours possible, the deepest blue, the warmest red, the most shining yellow, the most saturated green.

Ardon believed in pure art devoid of any political or social message. He believed that a painting should be appreciated and judged solely by its inherent artistic elements, such as colour, composition and their interplay. He rejected literary, symbolic or, indeed, any other additional meaning attributed to a work of art.

Ardon loved colors and ‘pure art’ but filled his works nevertheless with mystical connotations, Jewish symbolism and enigmatic scenery. He was appalled by the horrors of war and injustice and these themes too seeped into his art. Ardon was an artist who chose to use modern, expressionistic and abstract styles, combined with a classic painting technique which created distinctly unique paintings.

As Ardon expressed in a letter he wrote to Willem Sandberg, Director of the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam in 1960:

… an odd thing happened on my palette: something foreign sneaked into the group of cadmiums, ultramarines and viridiums – it was Jerusalem – ascetic, with a sack over its head.

What is Jerusalem doing amongst the bright cadmiums? How can one scratch it off the palette? Sometimes it can be scared away and hidden behind the ivory black. But in vain – the next morning it settles down again in the midst of the cadmiums…

One cannot get away from it. The alien Jerusalem always gives orders: “Thou shalt”, “Thou shalt not”, like a black woodpecker Jerusalem keeps knocking on your bark – Thou, Thou, Thou. Thou and the orphan, Thou and the widow…

In 1963 Ardon retired and finally was able to focus solely on his artwork. During these years, moving between Paris and Jerusalem, he created eight monumental triptychs – the last ‘Hiroshima‘ when he was 92. One of these was executed in stained glass by Charles Marq (who had collaborated with Chagall 20 years earlier) at Atelier Simon in Rheims, France between 1982 and 1984. A set of three large stained-glass windows (measuring (6.5×17 meters) cover one wall in the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem, dedicated to Isaiah’s vision of eternal peace with visual elements from the Kabbalah.

And many people shall come and say, “Come let us go up to the Mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob, that he may teach us his ways and that we may walk in his paths. For out of Zion shall go forth the Law and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. He shall judge among the nations and decide for many peoples and they shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more. Isaiah 2:3-4

Click on the thumbnail above to display a larger image (these are quite incredible stained glass images).

The left panel depicts the winding roads taken by the nations on their way up to Jerusalem, up to the Mountain of the Lord, each road marked with its own language and alphabet (Latin, Greek, English, French, Arabic).

In the central panel Ardon represents Jerusalem, where the city’s stone walls are represented by the Isaiah Scroll (one of the Dead Sea Scrolls), a spiritual wall combined with the Kabbalistic tree of the sefirot, a symbol of the mystical divine presence, a merging of the earthly and heavenly Jerusalems.

The right panel is the vision come true, guns and shells beaten and transformed into spades which hover above.

Ardon was considered by many to be Israel’s greatest painter.

For images of Ardon’s paintings check out the website http://www.ardon.com/

Qumran, where the Dead Sea scrolls were found, bears unmistakable evidence of major earthquake destruction in 31BC during the reign of Herod the Great where 10,000 people lost their lives (Josephus). Photo shows staircase to mikve (ritual bath) damaged by seismic activity.

Qumran, where the Dead Sea scrolls were found, bears unmistakable evidence of major earthquake destruction in 31BC during the reign of Herod the Great where 10,000 people lost their lives (Josephus). Photo shows staircase to mikve (ritual bath) damaged by seismic activity.