Walking the streets of the Old City your first introduction to Armenian ceramics may be the tiles designed by Mr. Karakashian that display the names of streets in Hebrew, Arabic and English. Please note that much of the painted pottery that you see in the souvenir shops in the Arab market is done in Palestinian workshops in Hebron.

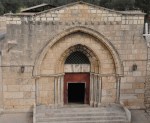

The Armenian community in Jerusalem goes back to the 5th century and in the Old City they live primarily in one of the 4 quarters, a walled neighborhood within the walls to the right from Jaffa gate called the Armenian quarter. Their religious center is the Cathedral of St. James that goes back to the 12th century. The Crusader King Baldwin II married the Armenian princess Morphia who bore him 4 daughters, the eldest, Melisende was married to Fulk, Count of Anjou who was King of Jerusalem and ruled in her own right from 1129-1161. She is buried in the Tomb of Mary in the Kidron valley. From at least the 17th century numerous ceramic tiles by Armenian artists from Kutahya and Iznik were sent as gifts to the Cathedral and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

After the British defeated the Turks, Ronald Storrs was the military governor of Jerusalem and one of the projects was to repair the 16th century ceramic tiles of the Dome of the Rock. David Ohannessian who had fled from the city of Kutahya, Turkey to Jerusalem and was known to Mark Sykes was recommended to Storrs. Ohannessian set up a workshop first on the Haram el Sharif and then later on the Via Dolorosa. Although the project fell through due to lack of funds he started producing ceramic wares and tiles to sell. An Armenian told me that the Muslims didn’t allow the Armenians who are Christian to work on the building.

Many recognize David Ohannessian as the founder of local Armenian ceramics based on the Iznik tradition and a bridge between the ceramic artistry of Turkey and what was to be developed later in Jerusalem. Ohannessian created tiles for buildings in Jerusalem until 1948 when he left for Beirut. You can see examples of these tiles at the Rockefeller museum and in my neighborhood, on the facade of originally Christian-Arab buildings, at 25 Emeq Refaim (I lead a tour of the German Colony that includes the Armenian story in the fascinating history of the German Templars) and next door to my house, at 24 Hazefira. Be on the lookout for other examples as you explore the city, buildings on Jaffa Road, in Talbiye, American Colony Hotel, St. John’s hospital (today the Mount Zion Hotel), Scottish Church of St. Andrew.

In 1922 Balian and Karakashian opened their own workshop at 14 Nablus Road where the families worked and lived for more than 40 years. Ballian was the master potter and Karakashian the painter artist and they passed on their skills and traditional craft to the next generation. It was here that the transformative process took traditional Kutahyan Armenian ceramics and created a uniquely Jerusalem pottery, the introduction of an art form that had not previously existed in the city. It is a major contribution to decorative art, creating an artistic language that combines Eastern and local elements.

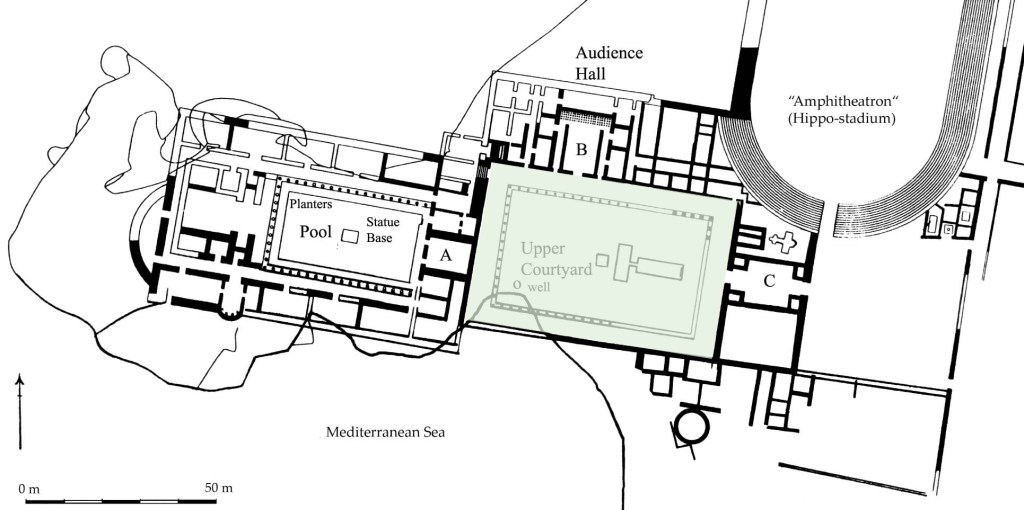

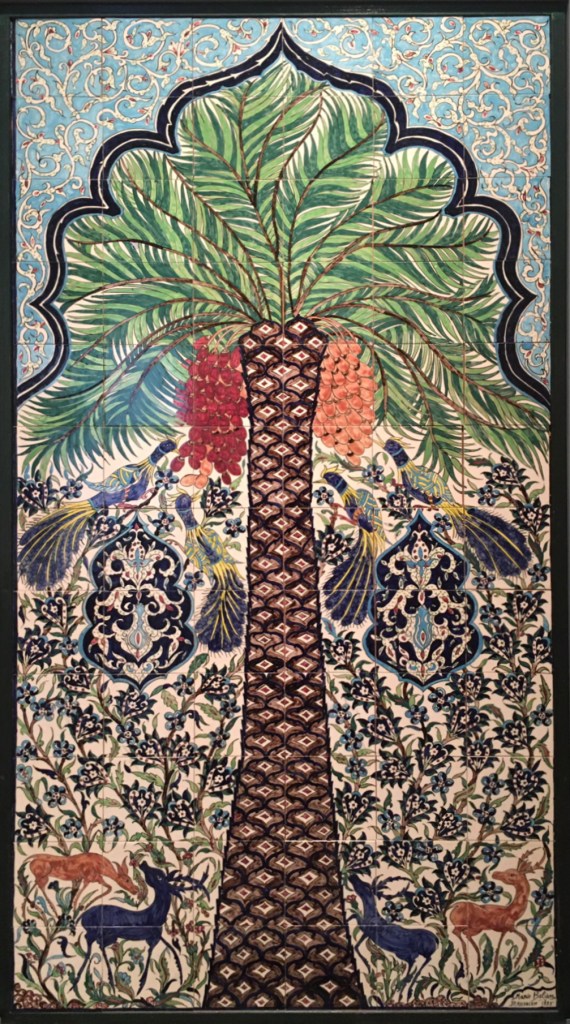

Their repertoire of forms was grounded in the traditional designs of Iznik (carnations, tulips, almond blossoms and saz leaves) and Kutahya (white or blue background with discretely outlines images) and included themes from the Bible. Two mosaic pavements in particular seems to have inspired them: the 6th century Bird Mosaic in the Armenian chapel and an Umayyad mosaic from the 8th century at Khirbat al-Mafjar (Hisham Palace) near Jericho. As they worked the two artists created new forms of their own inspired by local sources. Their first major project was a series of tile panels for the walls of the courtyard where the Patriarchs are buried in the Armenian Cemetery on Mount Zion. Their last work together done in 1963 were three rectangular tile pictures in the center of which are arched niches enclosed behind latticework doors for the facade of the Cathedral.

The designs were created by the master painter as drawings on paper. The paper design would be perforated along the lines so that the copyists could transfer them to the ceramics. The copyist-artisans would then paint the outlines in black and then colored glazes would be painted onto the ceramic. When the Balians and Karakashians separated in 1964, the traditional patterns, property of the joint workshop were divided between them.

In 1965 the Karakashian family moved to live and work in the Old City, where they created a studio, “Jerusalem Old City” on the Via Dolorosa between El Wad and Khan El Zeit (recently they moved to 3 Greek Orthodox Patriarchate Street in the Christian quarter). The main designs are those of arabesques, various bird designs, flowers, grapevines, a fawn, fish and biblical scenes on ceramic vessels and tiles.

http://www.jerusalempottery.biz/about_us/aboutus.htm

The Balian studio, called Palestinian Pottery, is still at the original 14 Nablus Rd location.

https://armenianceramics.com/about/

The creative force behind the Balian workshop was Marie Balian, who had studied painting in Lyon, France. One outstanding example is her dialogue with the images of the tree, gazelles and lion from the Hisham Palace painted in various combinations. By the early 1980s Marie Balian was working on larger compositions of many tiles, as if they were monumental canvases.

In 1986 she created a multi-tile triptych for the “Sukkoth patio” of the President of Israel’s residence which included pomegranates, date palms and grapevines (from the seven species that grow in the Land of Israel).

For an excellent book on the subject check out

Kenaan-Kedar, Nurith, The Armenian Ceramics of Jerusalem: Three Generations 1919-2003, Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Jerusalem, Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv, 2003. ISBN 965-217-217-0

Sato Moughalian, the grand-daughter of David Ohannessian published a book in 2019 about his life and art, Feast of Ashes.